Eduardo Robledo: Art With a Sense of Community

9/4/2021

Written by Karina Ruiz Ojeda

The artworks of Mexican printmaker Eduardo Robledo are imprints of his homeland and its millenary cultural heritage. Each print seems like a fragment of a dream, a brief revelation, or a glimpse of a ritual. Agriculture, flowers, spiritual animals, skulls and magic objects are motifs that are linked up in a particular sense of order, through symmetry and unifying shapes; like a micro interdependent community.

Eduardo was born and raised in Xochimilco, a borough located in South Mexico City. An ancient culture that has adapted and resisted urbanization processes, its fertile land, to this day, still provides the city with agroecological products, through its pre-Hispanic agricultural system of canals and artificial islands. It is also a protected natural area, and people preserve their identity with unique and vast customs and celebrations. This is the background for Eduardo's visions of life and art

Understanding the social meaning of printmaking

Eduardo had explored several artistic disciplines, but it was only after graduating from the National School Of Plastic Arts of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, when he realized he had a passion for printmaking. It was then that some teachers invited him to take part in a printmaking workshop to support indigenous communities, with grants, and free art courses and meals for children in poverty. During the late 2000’s, he also participated actively in the National Movement in Defense Of Oil, for which he produced anti-establishment images to support the social movement.

There’s a sense of community in Eduardo’s art, partly due to his deep understanding of the social meaning of printmaking in Mexico. “Printmaking is democratic, it’s more supportive, there is a very strong graphic arts tradition in social movements”, he points out. The artist stresses the quality of multiplicity in this discipline; because it lets them print numerous copies, the images can be present at the same time in the streets and museums alike. It also provides the artists with a diverse range of possibilities. “It has a wonderful versatility, you can even print by hand”, he explains.

Back to his origins

Later in his career, Eduardo decided to refocus his work, and to come back to his origins, portraying two of the things that he loves: his grandfather’s stories and the traditions of Xochimilco. He remembers: “I spent very beautiful times with my grandparents, I lived with them for a long time. My grandfather was very chatty, he had tons of stories. It was a spontaneous tradition that after supper we chatted for 15 or 20 minutes, almost everyday”. This is clearly depicted in “Dile Que Lo Espero”, a piece dedicated to his deceased grandfather. “The meaning of this artwork is very intimate. I am telling a superior entity to tell my grandfather that I am going to be right here, waiting for him. So the devil is me, holding the basket of stories that he told me”, he explains.

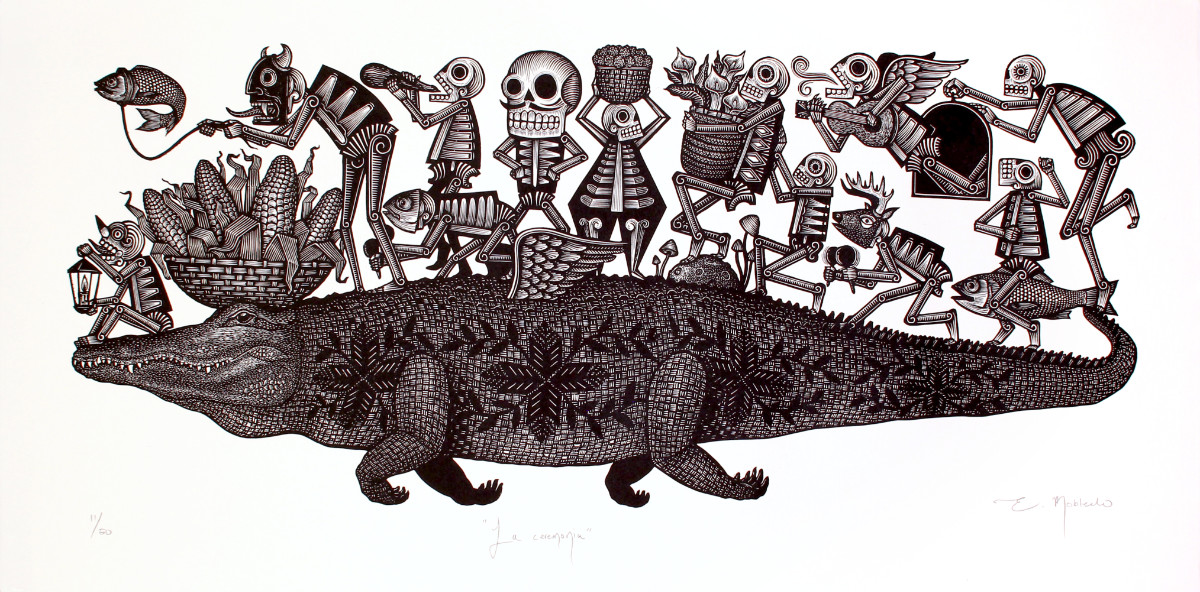

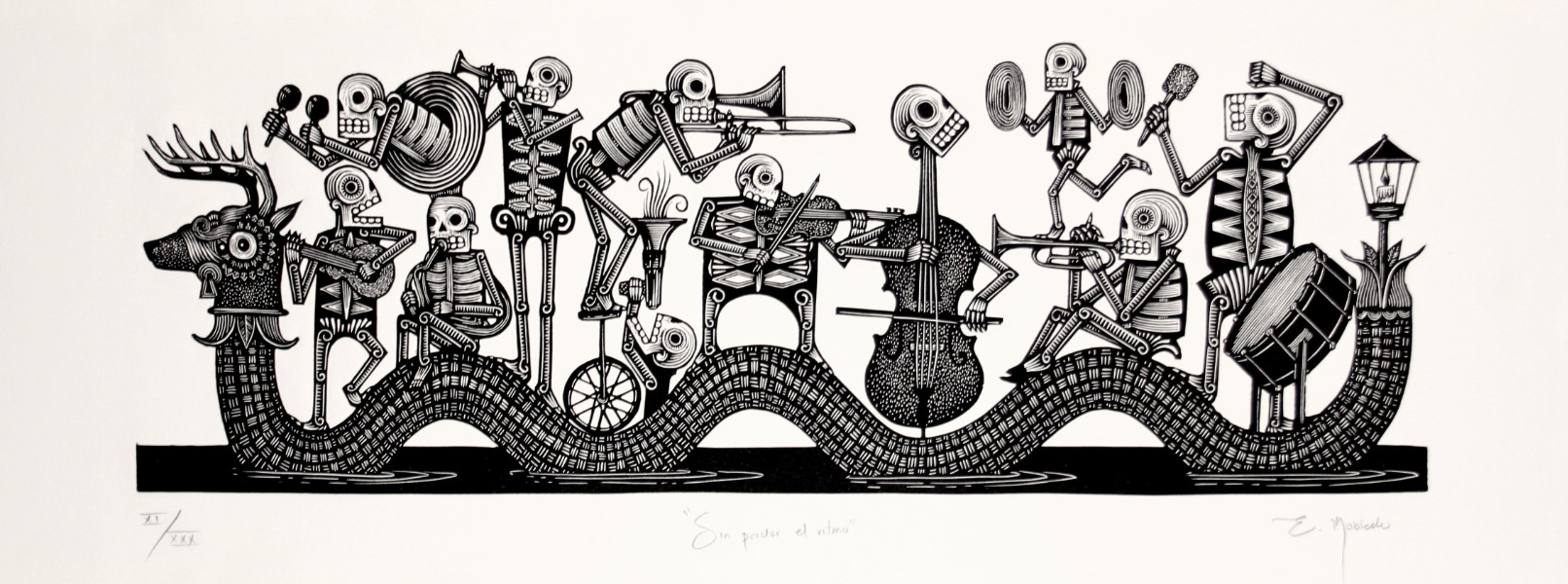

It is said that Xochimilco has more celebrations than the year has days. Throughout the 17 neighborhoods and 14 originary villages that integrate this borough, there are about 400 different traditional ceremonies each year. The atmosphere of these traditions can be seen in the work “Sin Perder El Ritmo”: a band of skulls plays music over a masked serpent, floating on the water’s surface. In several other artworks we see masks that make us think about the carnivals and festivals of Xochimilco.

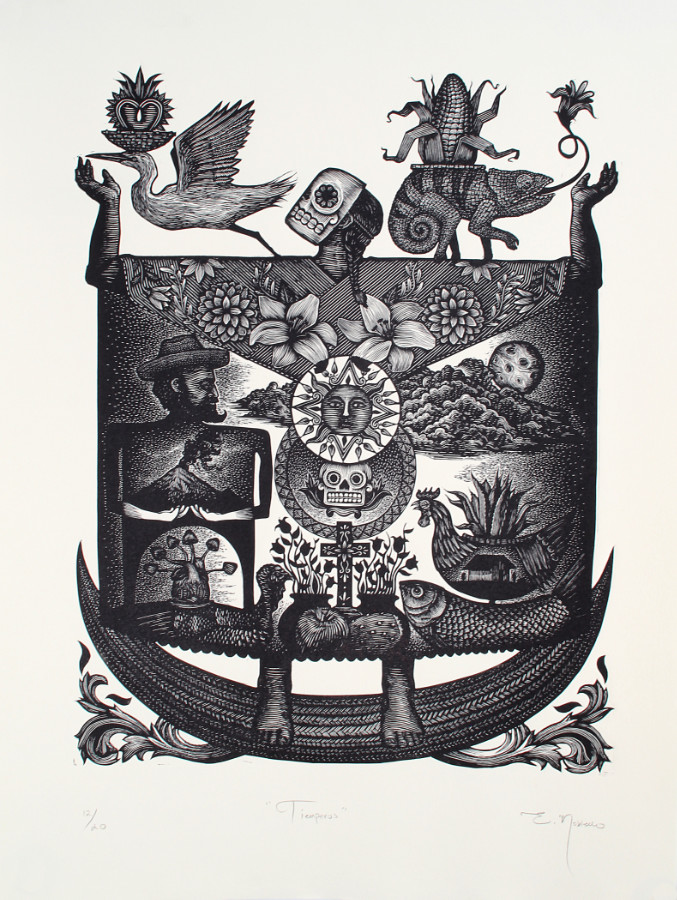

Eduardo’s interests include ancient knowledge, such as herbolary and cosmic geometry, as well as rituals and ceremonies, which are all connected to the oniric. Diableros and chamanes (wise men who cure with plants) are also important inspirations to him. An example is his work “Tiemperos”, which depicts the graniceros, people who have the gift of manipulating the weather. According to tradition, they maintain the necessary balance for rural life to prosper, and pray for rain; through dreams they heal, have premonitions, and communicate with nature. They are the link between humans and superbeings.

Agriculture and spiritual animals

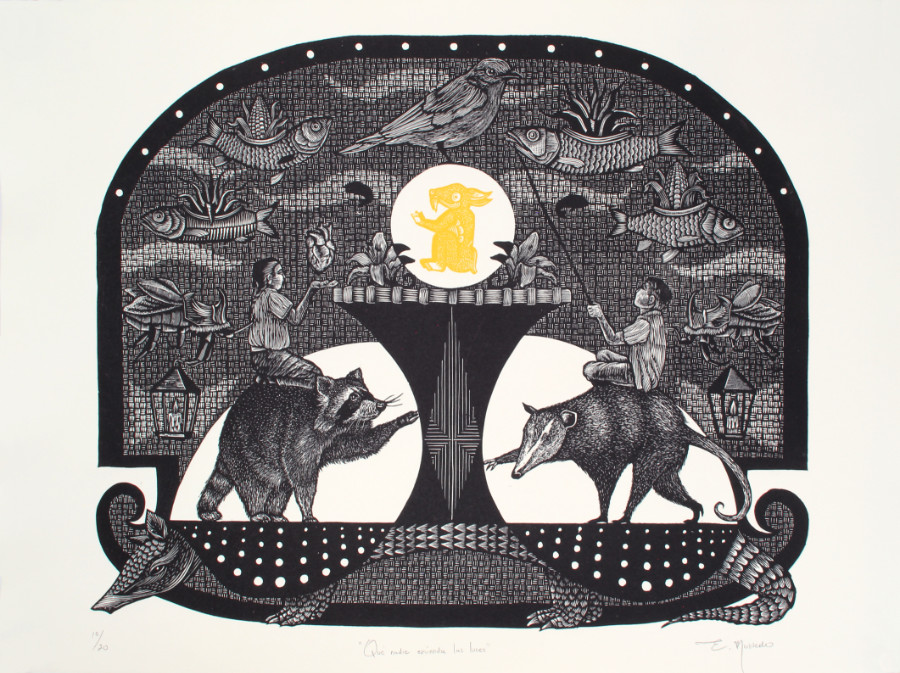

The most characteristic feature of Xochimilco's agricultural system is the chinampas: artificial islands of high fertile soil, built by the Aztecs in the 16th century. Eduardo’s grandfather was a chinampero (chinampa farmer) in his youth; in his work "Colectividad", we see him working the land, in the company of two spiritual animals: a hare and a xoloizcuintle (aztec dog), under the protection of two superior entities that provide rain and fertility.

Eduardo describes nature as a collective engineering work, a system where everything is there for a reason, "if those little details didn’t exist, everything would collapse”, he comments. For the artist, the farmer’s role is central in this game: it is about deeply knowing all these natural processes, permanently listening to them, and therefore having the ability to establish a beautiful communication with the environment. His work illustrates the values of his culture, such as sustainability: making a low impact while preserving ancient traditions.

Among the primal elements in Eduardo’s images are different types of plants and vegetables, each one of these having a great cultural and biological importance. Maize: our ancestral food. Agave: scraped by the tlachiqueros to extract pulque and aguamiel, sacred drinks from the gods. And cempasúchil (marigold): one of the pre-Hispanic species that make up the rich Xochimilco landscape, where the economy of a great number of families depends on growing and selling flowers.

Owls, deer, fish, turkeys, armadillos, crocodiles, birds, iguanas. Most of the animals in Eduardo’s prints refer to a recurrent theme in his grandparent’s stories: the nahuales, personal spiritual guardians residing in animals. These motifs aren’t just references, they are part of his personal beliefs. “Those nahuales stories are present in almost all of my artworks. Our ancestors thought that depending on the day you were born, a certain animal would accompany you, that would be your nahual. There is also the belief that the wizards or wise men are able to transform into animals”, he explains.

Days of the Dead

Days Of The Dead festivities are unique and vibrant in Xochimilco, as Eduardo narrates, “You spend the night at the cemetery, and you get all the visual enjoyment of the flowers, and their aromas. In the years before the pandemic, at each pier or little square they would set up big stages, and there would be theatre and music all night long; it was very family-friendly and beautiful”. During these celebrations, sharing food and drink serves as a symbolic reunion between the worlds of the living and the dead. To the artist, it is fascinating that many Mexicans have this type of communion, he himself is completely sure there is an afterlife.

Traditions around death are at the core of Eduardo’s aesthetic references. Sometimes, when he’s starting a piece, he draws a skull almost unconsciously. “Since I was a kid, funeral processions have been beautiful to me. When someone dies, there’s a whole cortege to take them to the cemetery: they are carried, ornamented with flowers, and music is played to them. I thought it was very romantic, and always said that I wanted to be the protagonist of that funerary march”, he recalls. These parades are a last goodbye to their neighborhood, their hometown, as a means to express gratitude for the place where they lived.

The calendar of religious and popular celebrations of the xochimilcas are connected to their farming seasons. For instance, the end of the corn harvest season, in late October, coincides with the beginning of the All Saint’s Day celebrations. On those days, there are a lot of ritual expressions to thank god and the deceased, who also intercede to have good harvests, according to the nahua tradition.

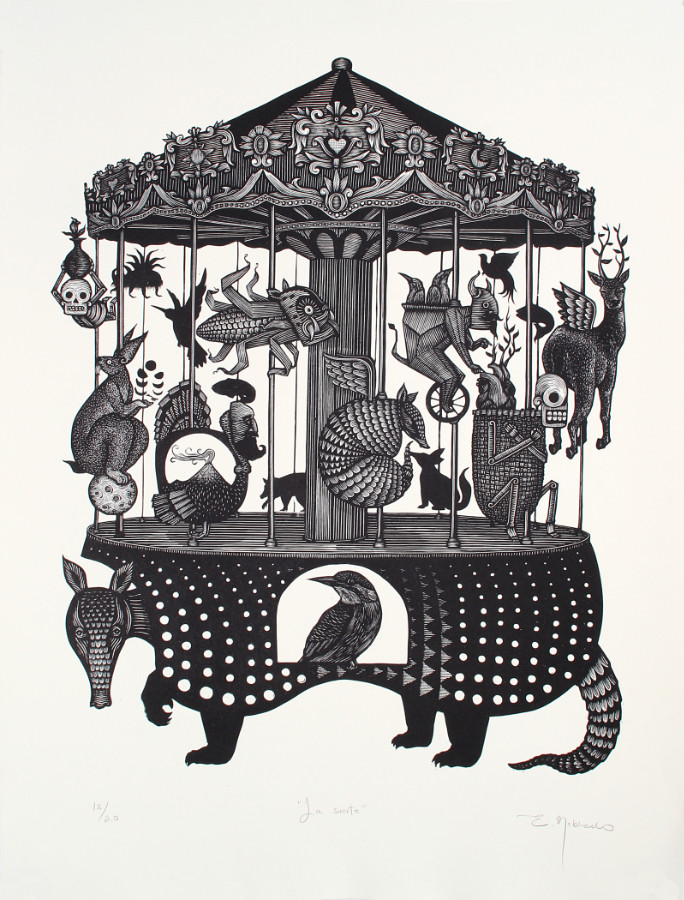

La Suerte

Glimpses of an ancestral culture

As a fanatic of Xochimilco’s antique photography, Eduardo would have liked to live in the 50’s. He acknowledges that his hometown has changed a lot in the last decades. Sometimes his prints remind us of the Xochimilco of Emilio Fernández’s film “María Candelaria” (1943): the adobe houses, the tile roofs, the lamps, the fresh air. Unfortunately, the irregular urbanization of the chinampas zone has brought the loss of part of the agricultural knowledge and landscapes, but Eduardo’s art brings them to life again. “I feel very proud to have been born in this place, because of all the wealth it has, in terms of natural resources, culture and history”, he points out.

Often, the stories within Eduardo’s works have a shape in common that contains his compositions and gives them unity, replicating a community sense, in which nothing is isolated. In “Tiemperos”, all the figures are displayed in a woman’s huipil (a pre-Hispanic women's garment), in perfect balance. In “La Suerte”, there is a “merry-go-round-armadillo” that contains all the spiritual animals and devils. Just like a sense of identity makes people gather in traditional celebrations, Eduardo brings together images of his origins in a particular sense of order; in a balance between nature and culture, the tangible and the oniric, the earthly existence and an afterlife; giving us glimpses of an ancestral and complex culture.

---

* Karina Ruiz Ojeda has a MA in Art History, is an independent researcher, art and music curator. She also teaches Spanish as a second language. She lives and works in Oaxaca City, Mexico.